In my previous article on the uniquely American suburbs, I delved into their controversial history. Here, I’ll focus on the political and social critiques of America’s particularly car-centric and sprawled form of suburban development. A third and final piece will look at the financial picture, as well as the suburbs’ viability, both for the country and investors.

Conspiracy theories that the suburbs were created to drive demand for automobiles are, for the most part, backward. It was, in actual fact, the mass adoption of the automobile that drove the creation of the suburbs. Of course, big business (Levittown) and government policy (the creation of the interstate highway system and urban renewal) also played a part in the expansion of America’s car-centric suburbs.

But even if the causes of America’s suburban sprawl were completely benign, that doesn’t mean that the suburbs as currently constituted are good nor sustainable nor a place for quality, long-term investments. It is to these questions we now turn.

Evaluating Critiques of the Suburbs: The Suburbs Are “Soulless”

One of the major critiques of the suburbs is that they are “soulless.” In other words, as Alex Balashov puts it in Quartz, “it’s designed for cars, not humans.” He continues:

“Far from posing a mere logistical or aesthetic problem, it shapes—or perhaps more accurately, it circumscribes—our experience of life and our social relationships in insidious ways… For just one small example of many: Life in a subdivision cul-de-sac keeps children from exploring and becoming conversant with the wider world around them, because it tethers their social lives and activities to their busy parents’ willingness to drive them somewhere. There’s literally nowhere for them to go. The spontaneity of childhood in the courtyard, on the street, or in the square gives way to the managed, curated, prearranged ‘play-date.’ Small wonder that kids retreat within the four walls of their house and lead increasingly electronic lives.”

This perspective is so ingrained that TV Tropes actually list the cut-and-paste suburb as a common cliché in TV and film, saying: “In fiction, especially animation and comics, the similarity will get ramped up: The houses, gardens, and cars will be identical. The lives of the residents may also be identical…” Think Stepford Wives, Pleasantville, and American Beauty.

While I think there’s a grain of truth to this, it’s wildly overstated. Social atomization and the much-discussed lack of community may have been aided by growing suburbanization, but it certainly wasn’t a major cause.

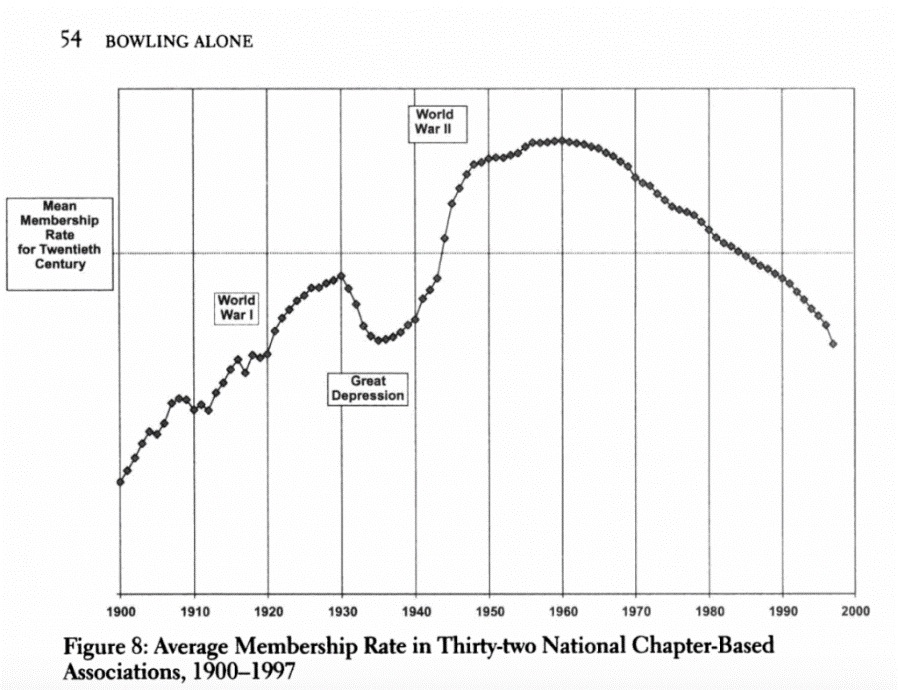

In Robert Putnam’s classic work Bowling Alone, he looks at the decline in social capital (i.e., “the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively”) in the United States. Putnam looked at a broad assortment of indexes, such as the number of friends people report having, the number of social occasions they attend, volunteer hours for things like PTAs, church attendance, marriage rates, family dinners per week, etc.

Putnam found that these indexes—which together measure a nation’s social capital—increased dramatically throughout the first half of the 20th century as America left behind the Gilded Age, before peaking in the early to mid-’60s and declining thereafter.

Here is Putnam’s chart on membership rates across 32 national chapter-based associations:

What’s noteworthy here is that the car-centric suburbs started growing almost immediately after World War II. Urban renewal started in the early ’40s, the first Levittown began selling houses in 1947, and the interstate highway system was started in 1956. None of this coincides with when social capital began decreasing. Therefore, it’s highly unlikely that suburbanization was a major cause.

Underlying this criticism is the assumption that the suburbs are, and have always been, atomistic and soulless. But I remember my own youth, living in a suburb and playing outside with other kids from around the block or who came over after school. I recently lived downtown and would never see such things. Indeed, families with kids have been leaving urban areas for decades, and as the Economic Innovation Group found, “Birth rates in large urban counties have declined twice as fast as in rural counties over the last decade.”

Urban housing tends to be small and lack a backyard, making it less than ideal for families with children. In some cases, it likely even lowers the birthrate, as Peter Zeihan makes the case for in Russia in the second half of the 20th century:

“The housing programs of Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, may have put roofs over heads, but the resulting apartments were so tiny that they lowered birthrates nearly as much as World War II.” (The Disunited Nations, Pg. 146)

Returning to the United States and the present, I’m now back in the suburbs and see kids playing up and down the street whenever the weather is nice. Indeed, while the “cut-and-paste suburb” is a TV trope, so is the nostalgic, suburban family life represented in shows such as Wonder Years and Family Matters.

It would seem that the decline in community life can be found elsewhere. Part of this is a decline in religiosity, as whether you’re religious or not, religious services are a good place to meet people, put down roots, and become part of a community. And just between 2007 and 2019, those saying they were “religiously unaffiliated” increased from 16% to 26%, while “monthly or more” church attendance declined from 54% to 45%.

Marriage is another thing that tends to bring people together, even if gatherings with in-laws have some negative stereotypes. While divorce rates have leveled off after skyrocketing in the late 1960s, the actual number of marriages has dropped precipitously. The marriage rate per 1,000 women has fallen from 76.5 in 1965 to 31.2 in 2022.

While this doesn’t count cohabitating, the overall trend is clearly down and likely to get worse. For example, a whopping 60% of men in their 20s are currently single. This may have a lot to do with technology, but as being single tends to inhibit family formation, it would appear that this type of social atomization is a vicious cycle.

While family formation is declining, Americans also tend to move away from their families. The rate of internal migration has actually declined slowly for decades now, but Americans are still among the most likely people to move from one city to another, often leaving behind family and friendship ties.

Wildly overhyped concerns about stranger danger, particularly in the 1980s, certainly didn’t help young people make friends and grow roots in a community. But by far, the biggest cause of social atomization is technology and many of the cultural changes that have come with it.

The number of friends and close friends Americans have has declined dramatically in the past 30 years, a trend that seems to have started around the 2000s—long after the modern suburb came into being, but around the time the internet took off and social media began to dominate our lives. One survey found—quite tragically—that 12% of Americans don’t have a single friend.

The evidence goes well beyond correlations. Indeed, the case that social media increases unhappiness and loneliness, particularly among the young, is overwhelming.

That said, I will grant the critics of suburbs one thing: There is something rather “soul-crushing” about suburban retail and commercial centers.

I don’t think the tidy little neighborhoods (like the one I live in) that you need to drive slowly through because of all the kids playing in the street is anything close to “soul-crushing.” Indeed, my wife and I very much enjoy taking our dog for a walk around the block to the local community park. But the commercial areas with row after row of strip malls and gas stations that look identical to just about every other suburb in the country feel incredibly bland and depressing, which leads to a much more valid critique.

The Suburbs Are Car-Reliant

Living anywhere in the United States without a car is difficult. Living in a suburb without one is almost impossible. Indeed, the suburbs were specifically built with the car in mind.

Advocates of urban density will point to European cities in particular and their much better public transport systems as a superior model. Of course, the U.S. is much bigger than any European country and less dense than almost all of them, which makes growing out a less expensive option than growing up (i.e., infill).

On the plus side, American suburbs are filled with an assortment of public parks and outdoor areas. On the downside, walking anywhere is not a reasonable option, while public transit is close to nonexistent. And, as noted, downtowns and commercial centers look like they were made on an assembly line.

One thing that could help bring suburban commercial areas to life is to phase out single-use zoning in these areas. This was a big point that Jane Jacobs made in her famous book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Areas that are solely for commercial use often lack foot traffic, as people solely drive to the store they want to go to. Furthermore, at night, they empty out and can become dangerous or prone to crime.

Not every commercial area should be mixed use, but in general, it creates a livelier area and enjoyable experience to shop, dine, and hang out in.

Regarding public transport, the United States isn’t just nearly as developed as Europe—it’s also in poor shape and becoming less popular while simultaneously more expensive. As the free-market Cato Institute noted even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit:

“Data released by the Federal Transit Administration in December 2019 indicate that 2018 transit ridership fell in 40 of the nation’s top 50 urban areas, and, over the past five years, ridership has fallen in 44 of those 50 urban areas… These declines have taken place in spite of huge increases in spending on public transit. In 2018 alone, subsidies to transit grew by 7.4%, increasing from $50.5 billion to $54.3 billion… Despite this increase, ridership fell by 215 million transit trips, or 2.1%.”

One major complaint I have about the urban advocates is their desire to force pro urban policies on the country instead of incentivizing them. Rarely do they discuss why Americans are so apt to move to the suburbs and are not particularly interested in using public transit. (Even as the price of used cars is almost 50% higher now than in 2019!)

Indeed, it’s the suburbs that have seen consistent growth while the cities have not. As Joel Kotkin pointed out (again, before COVID hit):

“151 million people live in America’s suburbs and exurbs, more than six times the 25 million people who live in the urban cores (defined as CBDs with employment density of 20,000+ people per square mile, or places with a population density of 7,500+ people per square mile…

…In the last decade, about 90% of U.S. population growth has been in suburbs and exurbs, with CBDs accounting for 0.8% of growth and the entire urban corps for roughly 10%. In this span, population growth of some of the most alluring core cities—New York, Chicago, Philadelphia—has declined considerably. Manhattan and Brooklyn have both seen their rate of growth decline by more than 85% since 2011. Nationally, core counties lost over 300,000 net domestic migrants in 2016 (with immigrants replacing some of those departees), while their suburbs gained nearly 250,000.”

Why?

Obviously, price is a huge component. Realtor.com notes that “[in] the 10 largest metro areas, suburban homes are an average 24.2% less expensive than homes in the urban core.”

But part of this is also a series of systemic problems in urban areas that many urban advocates oddly disregard. Apparently, there’s an X account documenting fights and other serious problems that are rather routine on New York’s subways these days, highlighting examples like this.

In New York, subway ridership is just 71% of its pre-COVID normal (which, as noted, was declining slowly beforehand). Yet despite reduced ridership, felony crime on the subways was up 47% from the year before and 14% higher than 2019, when ridership was 41% higher!

At the same time, there were 74 incidents in 2023 that caused service disruptions, the worst in five years, and the Citizens Budget Commission estimated the city lost approximately $700 million to fare evasion (on the subway, the taxpayer subsidizes to the tune of $289 million a year).

And yet, enforcement to reduce the number of fare evasions is muted, to say the least.

This leads to the next problem urban advocates tend to ignore: crime.

Suburbs Cause Crime

One study I came across concludes that suburbanization actually causes an increase in crime, saying, “we find a positive relationship between suburbanization and metropolitan crime.”

At first, this sounds a little farfetched, but upon reflection, it makes sense when taking everything into account.

It’s well understood and almost universally agreed upon that the increased crime (itself likely exacerbated by lead poisoning) and riots of the ’60s and ’70s led to a massive increase in suburbanization. With such a flight of people and capital to the suburbs, the cities were hollowed out. Poverty is not the only cause of crime, but it is one. Thus, a vicious cycle is created whereby urban crime causes suburbanization, which causes urban crime to increase more.

Many things are required to break such a cycle, including investment and efforts to improve schools. However, this cycle requires some toughness too. While there are obviously instances of police brutality, proactive policing is a necessary component for blighted areas to improve.

Proactive policing received a shot in the arm when James Q Wilson and George L. Kelling introduced the broken windows theory, noting, “Social psychologists and police officers tend to agree that if a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.”

In essence, the theory states that allowing disorder and small crimes to fester leads to more and bigger crimes. There’s plenty of debate about this theory, but in general, the evidence corroborates it. As a 2015 meta-analysis of 30 studies found, “policing disorder strategies are associated with an overall statistically significant, modest crime reduction effect.”

Unfortunately, much of this was, to pardon the pun, thrown out the window in 2020 in the wake of the George Floyd riots and the “defund the police” movement.

Of course, no police departments were actually defunded, and only a handful saw noteworthy budget cuts. But what almost certainly did happen was that police departments began to retrench, avoid hot spots, and take fewer chances. I’ve certainly noticed this, as police responsiveness where I live has markedly declined in the last few years.

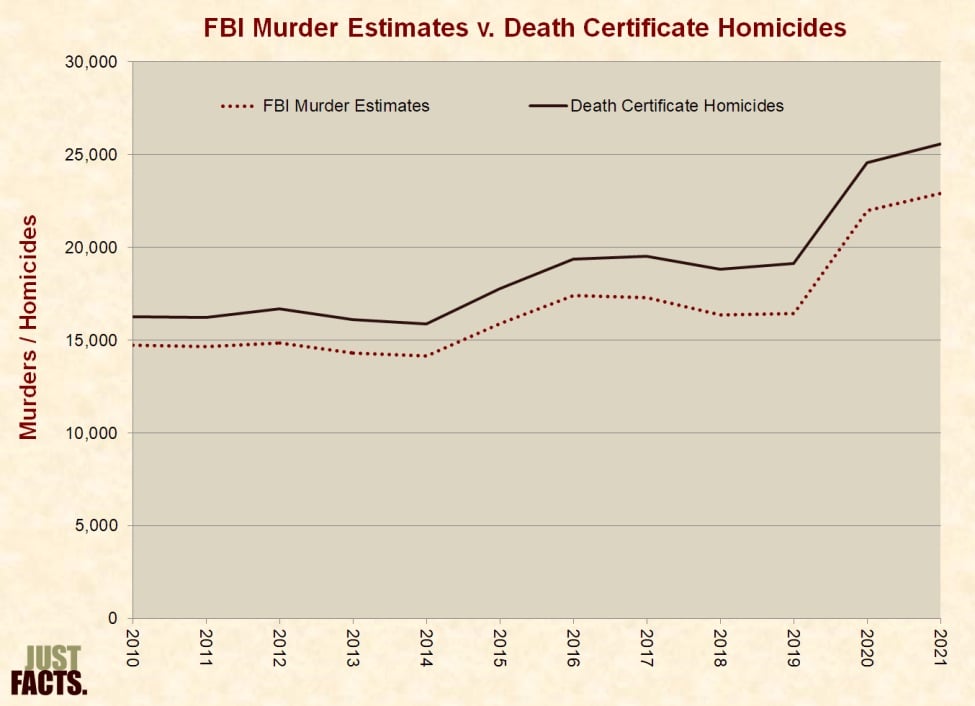

Broken window policing (an item many activists wanted removed) was, to at least a large degree, abandoned. The results weren’t pretty.

Murder rates have fortunately cooled off over the last two years, although there are some questions regarding that, as the FBI began a new crime reporting system in 2021 that even now, over one-third of the nation’s 18,000 police agencies aren’t reporting to, including New York, Los Angeles, and many other large municipalities.

At the same time, fewer Americans are reporting crimes than they were 10 years ago. Furthermore, this crime spike has been particularly acute in urban areas, with violent crime going up 58% in such areas between 2019 and 2022. Suburban areas didn’t see much of a rise at all.

Still, it appears crime has fallen in the last two years and is certainly well below where it was in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. But violent crime is higher than 10 years ago, and that’s with the mass incarceration that activists are (in large part correctly) upset about.

That said, crime problems are likely to fester, as across the country, police departments are facing severe personnel shortages. Officer resignations are up 47% over 2019, and 12 small towns went so far as to dissolve their police departments due to a lack of officers. In 2021, in Kansas City, where I live, the city lost 120 officers and only added 19. There are about 300 vacant positions (out of 2,000). New York, like most cities, I suspect, has a record number of officers eyeing early retirement.

The homeless population has also grown precipitously over the past 10 years, increasing almost 75% since 2014. Unfortunately, the opioid epidemic and very unwise government policy have created a disaster. Many downtowns, most notably San Francisco and Portland, Oregon, have become filled with homeless encampments. Compared to living in such a place, a “soulless” suburb would beat such a place any day.

Final Thoughts

Crime and the deterioration of public transit and major infrastructure make urban living substantially less desirable. These are issues that the suburbs don’t have nearly as much of.

Yes, a car is all but required to live in a suburb, and the commercial areas are a bit “soul-crushing.” But many of the critiques miss the forest for the trees. There are good things about the suburbs, including those backyard barbecues they’re so stereotypically famous for. Furthermore, there are ways to address the problems there (like phasing out single-use zoning) without ending the suburbs themselves.

But perhaps this discussion doesn’t matter. As the biggest complaint advocates of urban density have with the suburbs is that they are allegedly unsustainable; a Ponzi scheme held aloft by debt that’s about to come crashing down like the housing market did in 2008. We will turn to that question in the third part of this series.

Join the community

Ready to succeed in real estate investing? Create a free BiggerPockets account to learn about investment strategies; ask questions and get answers from our community of +2 million members; connect with investor-friendly agents; and so much more.

Note By BiggerPockets: These are opinions written by the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of BiggerPockets.